Load-Bearing Elements – Narrative Voice

|

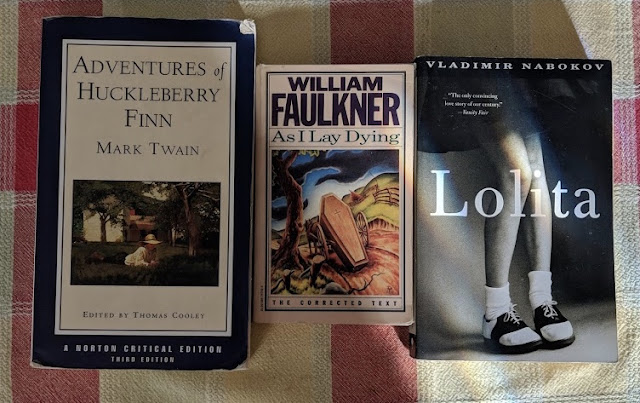

| Pictured: Examples to be discussed below. |

Yeah, Narrative Voice. Why? Is that not a good topic?

Well, it's a little broad isn't it? And I'm not sure it's something that can "bear the load" of a work of fiction, so to speak.

Well, maybe not on its own, but to belabor the metaphor, the individual support beams don't hold up the entire weight of a building either.

Hmm. You may continue.

All right, so let's begin by distinguishing point-of-view from Narrative Voice.

Umm, aren't they the same thing?

Kinda. They're related. Point-of-view is a component of Narrative Voice. While point-of-view determines just who is telling the story, Narrative Voice is more about how they tell it. An obvious example is Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Huck Finn narrates the story in his own words and in his own dialect. This is different from the presentation of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer which has a third-person narrator. This shift allows for a more complex story. In Huckleberry Finn, Huck confronts moral questions, particularly the issue of slavery, and we get to see the process by which he rejects conventional values of the time and comes to form his own moral judgments. The reader, being more worldly than Huck, will understand the significance of things he misses. It also helps the reader identify with the protagonist. Tom Sawyer is likewise a story about growing up and becoming more responsible, but the reader is kept at a remove from Tom by the third-person narration. We see Tom changing, but we experience the change along with Huck.

Well, that's all well and good, but what if you don't want the reader to identify with the narrator?

Well, there are a few different ways to accomplish that. More modern works will make the narrator unreliable. Lolita is related entirely through the viewpoint of Humbert Humbert. And while he may be charming and witty, that charm and wit is deployed in service of Humbert's own self-delusion and solipsism. Humbert lays the blame for his own actions on others and even claims that his twelve-year-old stepdaughter (the title character) initiated their sexual relationship. Now, it should also be noted that Nabokov doesn't just present Humbert's story as is. The novel uses a Metafiction, positioning the main body of the text as a memoir written by Humbert ahead of his murder trial. So the reader has even more of a heads up that he probably isn't on the level.

So, letting the narrator damn themselves by demonstrating their own unreliability.

Yes, another technique is to have a narrator who isn't the protagonist of the story. Let's go back to high school reading territory for this one: The Great Gatsby and To Kill a Mockingbird. Both Nick Carraway and Scout Finch are profoundly affected by the stories they relate. But they exist on the periphery of those stories. Gatsby is only interested in Nick to the extent that Nick can provide him access to Daisy, and Atticus purposely tries to limit Scout's access to the trial of Tom Robinson. Like Huck Finn, Scout is an engaging and likable character whose moral education is part of the point of the story; and, like Humbert, you can see Nick going out of his way to present himself in the best possible light (yeah, Nick, you've only been drunk twice, ;-p) . However, both Scout and Nick are telling stories about things that happened to other people.

I think you know what my next question will be.

Is it about stream of consciousness?

No.

Okay, but stream of consciousness is also an important thing in Modern literature.

I know, but—

Like, say, in Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury or As I Lay Dying where he spreads the narration out between several characters, some of whom don't fully understand the parts of the story they experience either because of their age or diminished mental capacity. Stream of consciousness places the reader even more directly in the characters' heads. Instead of being told a story after the fact, the reader experiences it in real time and—

|

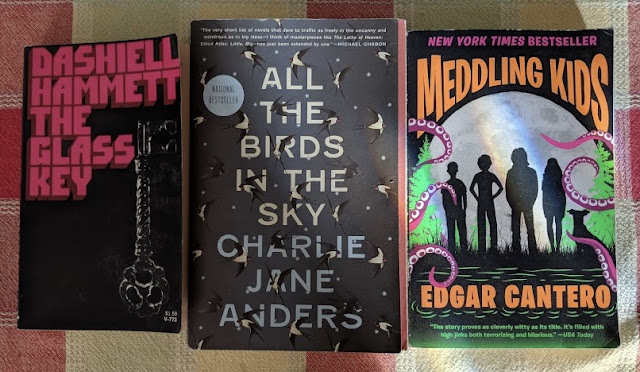

| Pictured: More examples to be discussed below. |

Oh, but.

You don't even particularly like stream of consciousness.

Well, no, but it's a fascinating idea and it im—

—merses you even more fully in the narrator's point-of-view. I get it. But back when you were talking about Huckleberry Finn you were talking about third-person narration and I thought it might be interesting to talk a little bit about Narrative Voice techniques from that perspective.

All right.

And it doesn't really need to be exhaustive, you know.

Okay. So, when it comes to third-person narration, it generally exists on what I'll call a spectrum of knowledge.

That sounds goofy.

I know, I just made it up. But third-person narrators can literally know everything (omniscient), and I mean everything: from the position and velocity of every electron in the universe to every single character's innermost thoughts and feelings. An example of this would be Frank Herbert's Dune, where a a scene might include the thoughts of any character. Alternately, the narrator might only know what an outside observer could see, smell, touch, hear, or taste (objective). Dasheill Hammett deployed this quite effectively in The Glass Key, where the narrator follows Ned Beaumont closely, but never directly relates the details of his inner life, only his actions, words, and expressions. Most third-person works will be in subjective (or limited) third-person. So, like in Harry Potter how most of the story is told by a narrator who knows what Harry (and only Harry) is thinking and feeling. Another common third-person technique is to rotate between two or more viewpoint characters, an example from a book I've reviewed on this very blog would be All the Birds in the Sky, which switches between the views of its dual protagonists, Laurence and Patricia.

Well, that was actually pretty succinct. I'm sure you'll find someway to complicate all this.

I wouldn't say complicate, but I should note that none of these is mutually exclusive. You can incorporate multiple types of Narrative Voices in a single narrative. Like Final Girls or Meddling Kids. In Final Girls, Riley Sager writes most of the action from a present tense first-person point of view, and then switches to past tense limited omniscient third-person for flashbacks. Meanwhile in Meddling Kids, the story is mostly written in past tense third-person with rotating viewpoints (plus this weird script format that ju—

Please don't remind me.

Sorry. Anyway, the narrative occasionally shifts into present tense second-person when one of the characters has a nightmare.

Huh, so are we going to talk about the second-person narrative voice techniques.

Well, I'm mostly familiar with them from all those Choose Your Own Adventure books I read when I was a kid. But it makes the reader the protagonist. In a non-CYOA context, this might feel disorienting, since, you know, there's a disconnect between what you'd actually do and what you're being told you are doing/have done. But, as with the opening scene of Meddling Kids, it does help put the reader in the character's headspace.

Okay, anything else to add?

Probably, but you know, Load-Bearing Elements is more of a "scratch-the-surface" thing. I think this will suffice for now.

All right.

Comments

Post a Comment