Load-Bearing Elements – Prose Style

|

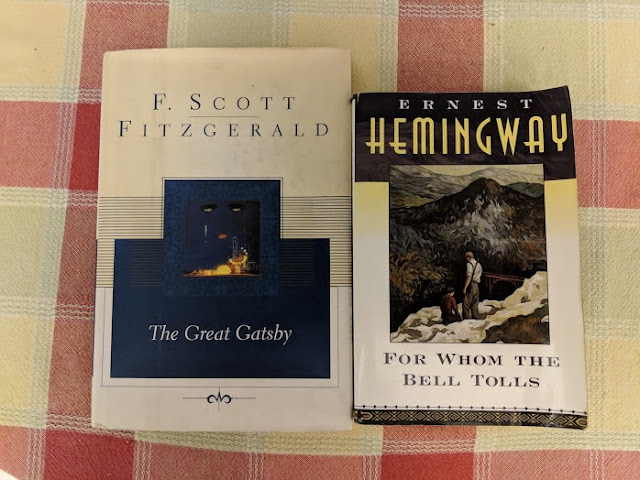

| Hey! Check out these assholes with their well-known books and easily recognized writing styles! |

Usually. . . Wait, what am I joking about?

You expect us to just sit here and listen as you wax rhapsodic about being transported by an author's prose?

Of course not, Hypothetical Reader. I just wanted to talk about prose style because I often find that it can be a major component of or stumbling block to enjoying a writer's work.

But isn't this a little close to the previous Load-Bearing Elements? The one on narrative voice.

I'll grant you that there are similarities, but it's what I felt like writing about when I sat down to write this. Besides, a writer with just about any style can still use just about any narrative voice. Before we jump into any examples, how about you describe my prose style on this blog.

You're sure you want this?

Yes. Would you mind terribly?

Okay, you asked for it.

I did.

Okay, so you definitely prefer long, compound sentences, even if you really could stand to break them up into multiple, shorter sentences. You tend to ignore the generally accepted writing advice of using adverbs sparingly. You try to adopt an off-the-cuff, conversational tone (which usually leads to lots of parenthetical statements and, let's be honest, doesn't help you to rein in those run-on sentences) and sprinkle in some jokey-jokes that you think make you seem breezy and approachable, but which actually make you sound snarky and pretentious.

Let me stop you right there, for a moment.

I tried to tell you it was a bad idea.

No, no, I appreciate your candor. But yeah, prose style can be deployed to create specific effects in writing. Whether or not an author's prose enhances or detracts from a work is also entirely subjective. Enough so that having a distinct style can be a double-edged sword. Obviously, writing with a distinct voice and personality can help you stand out in a marketplace crowded with generic commercial prose.

This right here is what I meant when I mentioned your snarky pretense.

I know. But the point is that standing out isn't always positive. For example, I hate, HATE, HATE the prose of H.P. Lovecraft and Cormac McCarthy. Each has a distinctive prose style, and each is insufferably terrible in their own right. But we're not gonna talk about them.

We're not?

Naw, fuck those guys!

So are we gonna go with the norm for this feature and start with some 19th century classic that everyone had to read in high school and work our way through to more contemporary works?

Nope, we're gonna talk about a couple of 20th century writers that everyone had to read in high school and call it a day.

You can't mean—

Yup! Everyone's favorite Lost Generation frenemies: F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway.

Dude! Everyone's read those two to death! It's such an obvious comparison, and we all know the basics: Fitzgerald: long sentences, big words; Hemingway: short sentences, small words. Ol' F. Scott used his elegant constructions to talk about he decadence and dissipation among the rich (or their hangers-on) in Manhattan, France, and Hollywood. Meanwhile Papa Ernie deployed simple language in service of exploring the doubts and emptiness that plagued American expats looking for meaning in the interwar years.

Maybe a tad reductive, but I couldn't have said it better myself, Hypothetical Reader.

I hate you.

That's fair. But I feel like the obviousness is part of what makes Hemingway and Fitzgerald work for a discussion of style. Everyone's read them — as far as our high school English teachers know, anyway 😉 —and because each one had a distinctive prose style, they're easy to form very strong opinions about. I confess that for a long time, The Great Gatsby was my favorite novel. Fitzgerald's writing bubbles off of the page like the free-flowing champagne at one of the title character's parties, flowing smoothly to take the reader along for the ride. This helps fuel the fantasy that it's all harmless fun, that Nick's just telling you about that irresponsible summer he spent on Long Island trying to make it as a bond salesman in the Roaring 20s. You know, until the incident.

That's how we're characterizing the end of the novel? I mean, you can just say until the deaths of Gatsby and the Wilsons.

‾\_(ツ)_/‾. As Ira Gershwin might say, "Py-jamas! Pa-jahmas!" Anyway, in For Whom the Bell Tolls–

Hold up! Don't people usually get assigned The Old Man and the Sea or A Farewell to Arms in high school.

Well, I read For Whom the Bell Tolls in high school.

For a class?

No, because I'm a nerd. Anyway, in FWtBT–

Nobody calls it that.

I hate you. So anyway, Hemingway's spare prose lends For Whom the Bell Tolls a sort of journalistic quality. It's obviously fiction, of course, but it has a sort of "just-the-facts" vibe. Like you're reading an (admittedly colorful) historian's account of how Robert Jordan helped helped a guerilla cell blow up a bridge in the Spanish Civil War.

What about all those parts about what Jordan is thinking, and all that business about how the Earth moved for him and María. Also the way that the dialogue is written as if someone were literally translating each individual word from Spanish to English, and –

Okay, okay, maybe not quite a historical record. But it feels much less like a story you're being told and more like one that you're observing as it happens. There's a certain inevitability in those clipped sentences.

You really don't mind coming off as pretentious, do you?

Nope!

Comments

Post a Comment